World of the Body: breast

The human breasts are mammary glands — common to all mammals, by definition. There are differences between species in number and in structure, and also in the composition of the milk that they produce for feeding the offspring.

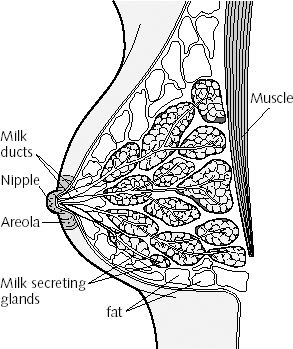

A pair of nipples is of course common to both boys and girls — a relic of the embryological development of the male having been superimposed upon the basic female. As girls approach puberty, female sex hormones produced in the ovaries circulate in the bloodstream and cause development the rudimentary breast glands, which have been present since before birth. Breast enlargement usually heralds the other changes. Progesterone promotes development of the potentially milk-producing cells, and oestrogens promote the development of the ducts leading to the nipple from the 15-20 ‘lobes’ of glands.

When menstrual cycles begin, the mammary glands also start to undergo cyclical changes: in the second half of the cycle, under the increasing influence of progesterone, the glandular tissue grows, sometimes causing ‘lumpiness’ and tenderness — one of many preparations for the pregnancy which in most months does not follow.

When conception does occur, the breasts continue to develop. The accompanying increase in blood supply distends the veins under the skin — often the first outward and visible sign of pregnancy. The glandular tissue proliferates, taking the place of connective tissue and fat, and the breasts progressively enlarge. Later in pregnancy, the hormones secreted from the fetal tissue of the placenta act on the glandular cells and on the ducts leading to the nipple: thus the fetus itself, along with the hormone, prolactin, from the mother's pituitary gland, prepares the ground for its own later nutrition. This same prolactin would also stimulate the production of milk — but oestrogens from the placenta counteract this, so that milk is not actually made before the time is ripe. After birth of the baby, this suppression stops, so prolactin activity is suddenly uninhibited. Unfortunately for ideal infant feeding, in ‘developed’ countries nowadays oestrogens are often taken orally, to suppress milk production in those mothers who choose to bottle-feed the baby.

The female breast. After Youngson, Encyclopedia of family health

Left to nature, the secretion is initially scanty (colostrum) but the volume of milk becomes significant at about the third day after the birth, when the breasts become quite dramatically engorged. The mother's pituitary hormones remain in control of milk synthesis and secretion; under this influence, fats, proteins, and lactose (milk sugar) are made in the gland cells from nutrients taken up from the blood. When the infant sucks, nerve impulses from the nipple reach the hypothalamus in the brain; these stimulate nerve cells that have stores of the hormone oxytocin in the ends of their fibres that lie in the posterior part of the pituitary gland. This causes release of the hormone into the circulating blood. Reaching the breasts, oxytocin activates contractile cells, which squeeze milk from its storage sites into the channels that take it to the nipple. This whole ‘neuroendocrine reflex’ takes about 10 seconds — barely long enough for a hungry infant to show serious signs of frustration.

Lactation will continue for just as long as a baby is regularly sucking away the supply of milk: the more is removed, the more is made. The volume averages about 1 litre per day, but twice that amount can be produced for twins. Weaning of the infant leads automatically to a decrease in the milk supply, and the glandular tissue reverts to the non-pregnant state — until the next time, if any.

The breasts in history and culture

The cultural significance of the breast revolves around its uses as a symbol both of fertility and of sexual pleasure.

Many prehistoric images represent the female body with a high level of body fat and large breasts, the ideals when the food supply was uncertain. Breast milk, as our first and most reliable food, has long been the subject of speculation about its nature and significance. The classical model dominant in Western medicine until the nineteenth century was dependent both on the Greek philosopher Aristotle, who argued that breast milk was a fluid intermediate between menstrual blood and semen in terms of the degree of ‘cooking’ it received in the body, and also on the Hippocratic medical writers. It was thought that special channels from the womb to the breasts carried and transformed blood; this meant that, after birth, a child continued to derive nourishment from the same blood that had been its source in the womb.

The medical imperative from such theories was, of course, that a mother should nurse her own child. However, in cases where the natural mother was unable to do this, or as a way of preserving the youthful appearance of the breasts, wet-nursing could be used. Contracts specifying the duties of a wet nurse, and her fees, survive from Roman Egypt, showing that this form of paid employment was available to women from early times. The second-century ad medical writer, Soranos, offered detailed, and historically influential, advice to Roman men on how to choose a good wet nurse. She should be aged between 20 and 40, have given birth two or three times, and be strong and in good health. Her breasts should be medium-sized, soft, and unwrinkled, with the nipples also of medium size and neither too compact nor too porous. Soranos argued that milk from large women is more nourishing, but regarded very large breasts as a health risk to the infant on two counts: first, they may fall on the nursling, and second, there will be milk left over after each feed, which will lose its freshness and then harm the infant at the next feed. Soranos believed that the wet nurse transmits her own qualities to the child, so an even-tempered woman free from superstition should be found; she should also be Greek-speaking, so that the nursling becomes accustomed to hearing Greek. The wet nurse must abstain from sex and alcohol, both of which could damage the milk. As well as studying the body of the potential employee, a Roman man must taste and smell her milk; after employing her, he should carefully supervise her diet. In the nineteenth century the recognition of the value of colostrum superseded the classical view that, not being ‘proper milk’, it should be withheld from the baby.

The advice Soranos gives represents both a continuing unease surrounding the use of wet nurses, and a continuing conflict between the nurturing and the erotic breast. Roman writers often accused women of wanting to employ a wet nurse only for the sake of maintaining a sexually desirable figure. Medium breasts on large women may have been good for babies, but classical art suggests that the erotic ideal was the small breasted, boyish woman.

In mid-eighteenth-century Europe when Linnaeus' classification of the natural world put humans among the Mammalia — those with breasts — debate over the use of wet nurses became a state concern. Linnaeus was in favour of mothers nursing their own children; with philosophers, naturalists, moralists, and medical writers, he argued that strong nations were built up from babies fed at the maternal breast. Using the maternal breast was economical, but also political, part of the good woman's civic duty, and linked to images of the state feeding its children.

When, as a result of Pasteur's discoveries, sterilization of animal milk for bottle-feeding became possible, even those who could not afford to pay a wet nurse could avoid breastfeeding. A further development was milk substitutes; however, in developing countries there have been considerable problems following the promotion of milk substitutes as an alternative to the real thing, due for example to the formula being made up with non-sterile water or at the wrong strength.

The patron saint of nursing mothers is St Agatha, the legendary martyr who had her breasts cut off, shown in renaissance and baroque art carrying them on a plate. Christian religious art has used the nurturing breast in many ways. In fourteenth-century Tuscan art, during a period of crop failures and plague, the image of the Virgin Mary suckling a greedy Jesus became widespread. Sometimes she is shown directing a stream of milk into Jesus' mouth, or into the mouth of a particularly privileged saint; such images can emphasize the humanity of Jesus, or evoke the analogy of the Christian sucking at the breasts of the church for spiritual nourishment. Images of Charity personified often show a child suckling at each of her breasts.

For Freud, the breast was the first erogenous zone, from which a child should move on to the anal and genital stages of its developing sexuality. The baby's complete satisfaction at its mother's breast led to an identification with the mother, after which the baby needed to develop a sense of itself as a separate being. This was achieved by a rejection of the breast, now seen as withholding milk. In adult life, a person therefore longs for the perfect pleasure of the breast which has been taken away. Ideals and representations of the erotic breast show far more variation than the lactating breast. It can be large or small, with a pronounced cleavage or with the breasts entirely separated. The ideal in the Middle Ages was to have firm, white, apple-shaped globes, far from the Hollywood images of Jane Russell or Lana Turner, and even further from the pneumatic breasts of top-shelf magazines. Sixteenth-century kings' mistresses, most notably Agnès Sorel, Diane de Poitiers, and Gabrielle d'Estrées, were painted showing their breasts; Agnès was even represented as the Madonna.

As the size and shape of the ideal breast has varied dramatically over time and space, so fashions have changed to reshape the normal range of breasts to fit the ideal. The breast has been compressed, surgically reduced, padded, enhanced with silicone, pushed up, and armoured by a range of devices including bodices, corsets, bras and, most recently, the Wonderbra. Even before the corset or the brassiere, in the Middle Ages pouches sewn in to dresses could give uplift. One of the best-known aspects of the early Women's Liberation Movement was the ‘bra burning’ of the late 1960s, a form of liberation intended to make men face up to the reality of the breast freed from its fantasy underpinnings.

Breast tissue is more prone than any other in the woman's body to develop cancer. This accounts for about 1 in 20 deaths of British women, becoming commoner with increasing age. Early detection is assisted by regular X-ray examination (breast screening — mammography), and various combinations of surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy can be effective in treatment.

The very high incidence of breast cancer in the Western world has made the breast into an organ associated as much with death as with nurturing life. Fanny Burney's harrowing description of her mastectomy, performed without anaesthetic in 1811, has survived; nowadays ‘lumpectomy’ may be adequate but mastectomy is sometimes necessary, and women who have had a breast removed may choose to use a prosthesis, or to adjust to a new body shape. The classical myth of the Amazons presents the woman with one breast as powerful, but feared. Currently some women with a family history of breast cancer are offered elective surgery to remove both breasts before disease appears; reactions to those who accept this surgery show that the breast remains a potent symbol of womanhood today.

— Sheila Jennett, Helen King