Brest Development

Though breast growth is not visible until puberty, breast development begins very early in the embryo and can be discerned within just a few weeks of conception. Interestingly, the earliest stages are identical in male and female fetuses, so many men could develop fully functioning breasts given the right hormonal conditions

After birth the breast has only two phases of development; the first at puberty with the outpouring of the hormones oestrogen and progesterone; the second during pregnancy and lactation, when the milk-producing lobules become larger

If puberty is stunted or if a woman remains childless, her breasts will not fully develop. The first stage of breast development begins in the embryo at about six weeks, with a thickening in the skin called the mammary ridge or milk line

By the time the fetus is six months old, this extends from the armpit to the groin, but it soon dies back, leaving two breast buds on the upper half oft he chest. Occasionally, rudimentary mammary glands develop along the milk line forming additional nipples or breasts that sometimes persist into adult life. More rarely, the two breast buds fade away with the rest of the milk line, so that the nipples are absent from birth

Because the initial development of the milk line is the same in male and female fetuses, this development can appear in the male and the female.

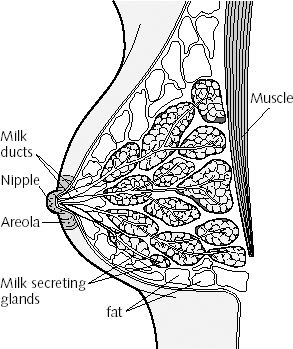

When a female fetus is about six months old, 15 - 20 solid columns of cells grow inward from each breast bud. Each column becomes a separate "sweat" or exocrine gland. With it’s own separate duct leading to the nipple

By the eighth month of fetal development, these columns of cells have become hollow so that, by birth, a nipple and a rudimentary milk-duct system have formed. No further development takes place until puberty

The first external signs of breast development appear at the age of 10 or 11 - though it can be as late as 14 years. The ovaries start to secrete estrogen leading to an accumulation of fat in the connective tissue that causes the breast to enlarge. The duct system also begins to develop, but only to the point of forming cellular knobs at the end of the ducts

As far as we know the mechanism that secretes milk doesn’t develop until pregnancy. Although the breast may appear fully grown within a few years of puberty, strictly speaking, their development is not complete until they have fulfilled their biological function - that is, until the woman carries a pregnancy to term and breast-feeds her baby, when they will undergo further changes

MATURITY OF THE BREASTS

Once a young woman reaches puberty, and ovulation and the menstrual cycle begins, the breasts start to mature, forming real secretory glands at the ends of the milk ducts. Initially these glands are very primitive and may consist of only one or two layers of cells surrounded by a base membrane.

Between this membrane and the glandular cells are cells of another type, called myo-epithelial cells, these cells are the ones that contract and squeeze milk from the gland if pregnancy occurs and milk production takes place .

With further growth, the lobes of the glands become separated from one another by dense connective tissue and fat deposits. This tissue is easily stretched. This is where the natural enlargement formula comes in and allows the enlargement that normally occurs during pregnancy when the glandular elements swell and grow

The duct system grows considerably after conception and many more glands and lobules are formed. This causes the breast to increase in size as it matures to fulfill its role of providing food for the baby

FEMALE CHANGES

Most women notice that just before menstruation their breasts enlarge and their nipples become sensitive and even painful. The texture of the breasts change and they become rather lumpy, with small discrete swellings that resemble orange pips in both texture and size. These lumps are glands in the breast which enlarge in preparation for pregnancy.

If pregnancy doesn’t occur, breasts return to their normal size and the glands become imperceptible to touch within a few days, ready for re-growth the next month. These changes in the breast are only one part of many changes that occur in the female body as the result of the monthly ebb and flow of the female hormones estrogen and progesterone

AGING OF THE BREASTS

As we get older, our breasts tend to sag and flatten; the larger the breasts, the more they sag. With the menopause there is a reduction in stimulation by the hormone oestrogen to all tissues of the body, including breast tissue; this results in a reduction in the glandular tissue of the breasts. So they loose their earlier fullness.

Regular exercise would have however prevented or slowed down the ageing process. Much of the connective tissue in the breast is composed of a fibrous protein called collagen, which needs oestrogen to keep it healthy. Without oestrogen, it becomes dehydrated and inelastic. Once the collagen has lost its shape and stretchability it "was" believed that it could not return to its former state or condition

STAGES - BREAST DEVELOPMENT

Human breast tissue begins to develop in the sixth week of fetal life. Breast tissue initially develops along the lines of the armpits and extends to the groin (this is called the milk ridge). By the ninth week of fetal life, it regresses (goes back) to the chest area, leaving two breast buds on the upper half of the chest. In females, columns of cells grow inward from each breast bud, becoming separate sweat glands with ducts leading to the nipple. Both male and female infants have very small breasts and actually experience some nipple discharge during the first few days after birth.

Female breasts do not begin growing until puberty—the period in life when the body undergoes a variety of changes to prepare for reproduction. Puberty usually begins for women around age 10 or 11. After pubic hair begins to grow, the breasts will begin responding to hormonal changes in the body. Specifically, the production of two hormones, estrogen and progesterone, signal the development of the glandular breast tissue. During this time, fat and fibrous breast tissue becomes more elastic. The breast ducts begin to grow and this growth continues until menstruation begins (typically one to two years after breast development has begun). Menstruation prepares the breasts and ovaries for potential pregnancy. Before puberty Early puberty Late puberty

the breast is flat except for the nipple that sticks out from the chest the areola becomes a prominent bud; breasts begin to fill out glandular tissue and fat increase in the breast, and areola becomes flat

Before puberty :The brest is flat except for the niple that stricks out from the chest

Early puberty:The areola becames a prominent bud; brests begin to full out.

Lately puberty:Glandular tissue and fat increases in the brest and areola becames fat.

Female Breast Developmental Stages

Stage 1

(Preadolescent) only the tip of the nipple is raised

Stage 2

buds appear, breast and nipple raised, and the areola (dark area of skin that surrounds the nipple) enlarges

Stage 3

breasts are slightly larger with glandular breast tissue present

Stage 4

the areola and nipple become raised and form a second mound above the rest of the breast

Stage 5

mature adult breast; the breast becomes rounded and only the nipple is raise

Though breast growth is not visible until puberty, breast development begins very early in the embryo and can be discerned within just a few weeks of conception. Interestingly, the earliest stages are identical in male and female fetuses, so many men could develop fully functioning breasts given the right hormonal conditions

After birth the breast has only two phases of development; the first at puberty with the outpouring of the hormones oestrogen and progesterone; the second during pregnancy and lactation, when the milk-producing lobules become larger

If puberty is stunted or if a woman remains childless, her breasts will not fully develop. The first stage of breast development begins in the embryo at about six weeks, with a thickening in the skin called the mammary ridge or milk line

By the time the fetus is six months old, this extends from the armpit to the groin, but it soon dies back, leaving two breast buds on the upper half oft he chest. Occasionally, rudimentary mammary glands develop along the milk line forming additional nipples or breasts that sometimes persist into adult life. More rarely, the two breast buds fade away with the rest of the milk line, so that the nipples are absent from birth

Because the initial development of the milk line is the same in male and female fetuses, this development can appear in the male and the female.

When a female fetus is about six months old, 15 - 20 solid columns of cells grow inward from each breast bud. Each column becomes a separate "sweat" or exocrine gland. With it’s own separate duct leading to the nipple

By the eighth month of fetal development, these columns of cells have become hollow so that, by birth, a nipple and a rudimentary milk-duct system have formed. No further development takes place until puberty

The first external signs of breast development appear at the age of 10 or 11 - though it can be as late as 14 years. The ovaries start to secrete estrogen leading to an accumulation of fat in the connective tissue that causes the breast to enlarge. The duct system also begins to develop, but only to the point of forming cellular knobs at the end of the ducts

As far as we know the mechanism that secretes milk doesn’t develop until pregnancy. Although the breast may appear fully grown within a few years of puberty, strictly speaking, their development is not complete until they have fulfilled their biological function - that is, until the woman carries a pregnancy to term and breast-feeds her baby, when they will undergo further changes

MATURITY OF THE BREASTS

Once a young woman reaches puberty, and ovulation and the menstrual cycle begins, the breasts start to mature, forming real secretory glands at the ends of the milk ducts. Initially these glands are very primitive and may consist of only one or two layers of cells surrounded by a base membrane.

Between this membrane and the glandular cells are cells of another type, called myo-epithelial cells, these cells are the ones that contract and squeeze milk from the gland if pregnancy occurs and milk production takes place .

With further growth, the lobes of the glands become separated from one another by dense connective tissue and fat deposits. This tissue is easily stretched. This is where the natural enlargement formula comes in and allows the enlargement that normally occurs during pregnancy when the glandular elements swell and grow

The duct system grows considerably after conception and many more glands and lobules are formed. This causes the breast to increase in size as it matures to fulfill its role of providing food for the baby

FEMALE CHANGES

Most women notice that just before menstruation their breasts enlarge and their nipples become sensitive and even painful. The texture of the breasts change and they become rather lumpy, with small discrete swellings that resemble orange pips in both texture and size. These lumps are glands in the breast which enlarge in preparation for pregnancy.

If pregnancy doesn’t occur, breasts return to their normal size and the glands become imperceptible to touch within a few days, ready for re-growth the next month. These changes in the breast are only one part of many changes that occur in the female body as the result of the monthly ebb and flow of the female hormones estrogen and progesterone

AGING OF THE BREASTS

As we get older, our breasts tend to sag and flatten; the larger the breasts, the more they sag. With the menopause there is a reduction in stimulation by the hormone oestrogen to all tissues of the body, including breast tissue; this results in a reduction in the glandular tissue of the breasts. So they loose their earlier fullness.

Regular exercise would have however prevented or slowed down the ageing process. Much of the connective tissue in the breast is composed of a fibrous protein called collagen, which needs oestrogen to keep it healthy. Without oestrogen, it becomes dehydrated and inelastic. Once the collagen has lost its shape and stretchability it "was" believed that it could not return to its former state or condition

STAGES - BREAST DEVELOPMENT

Human breast tissue begins to develop in the sixth week of fetal life. Breast tissue initially develops along the lines of the armpits and extends to the groin (this is called the milk ridge). By the ninth week of fetal life, it regresses (goes back) to the chest area, leaving two breast buds on the upper half of the chest. In females, columns of cells grow inward from each breast bud, becoming separate sweat glands with ducts leading to the nipple. Both male and female infants have very small breasts and actually experience some nipple discharge during the first few days after birth.

Female breasts do not begin growing until puberty—the period in life when the body undergoes a variety of changes to prepare for reproduction. Puberty usually begins for women around age 10 or 11. After pubic hair begins to grow, the breasts will begin responding to hormonal changes in the body. Specifically, the production of two hormones, estrogen and progesterone, signal the development of the glandular breast tissue. During this time, fat and fibrous breast tissue becomes more elastic. The breast ducts begin to grow and this growth continues until menstruation begins (typically one to two years after breast development has begun). Menstruation prepares the breasts and ovaries for potential pregnancy. Before puberty Early puberty Late puberty

the breast is flat except for the nipple that sticks out from the chest the areola becomes a prominent bud; breasts begin to fill out glandular tissue and fat increase in the breast, and areola becomes flat

Before puberty :The brest is flat except for the niple that stricks out from the chest

Early puberty:The areola becames a prominent bud; brests begin to full out.

Lately puberty:Glandular tissue and fat increases in the brest and areola becames fat.

Female Breast Developmental Stages

Stage 1

(Preadolescent) only the tip of the nipple is raised

Stage 2

buds appear, breast and nipple raised, and the areola (dark area of skin that surrounds the nipple) enlarges

Stage 3

breasts are slightly larger with glandular breast tissue present

Stage 4

the areola and nipple become raised and form a second mound above the rest of the breast

Stage 5

mature adult breast; the breast becomes rounded and only the nipple is raise